What a military general taught me about quiet leadership

On 'leadership that is not loud, but works'

A few years ago, I had the honor of connecting with the extraordinary Elanor Boekholt O’Sullivan - the first three-star general in the Dutch Armed Forces, and a self-described “highly sensitive, introverted leader with a strong voice.”

General Boekholt O’Sullivan has received various honors for her work in supporting quieter voices in the military - including hosting a Quiet Leadership Symposium (at which I had the honor of speaking, along with General Stanley McChrystal and many others).

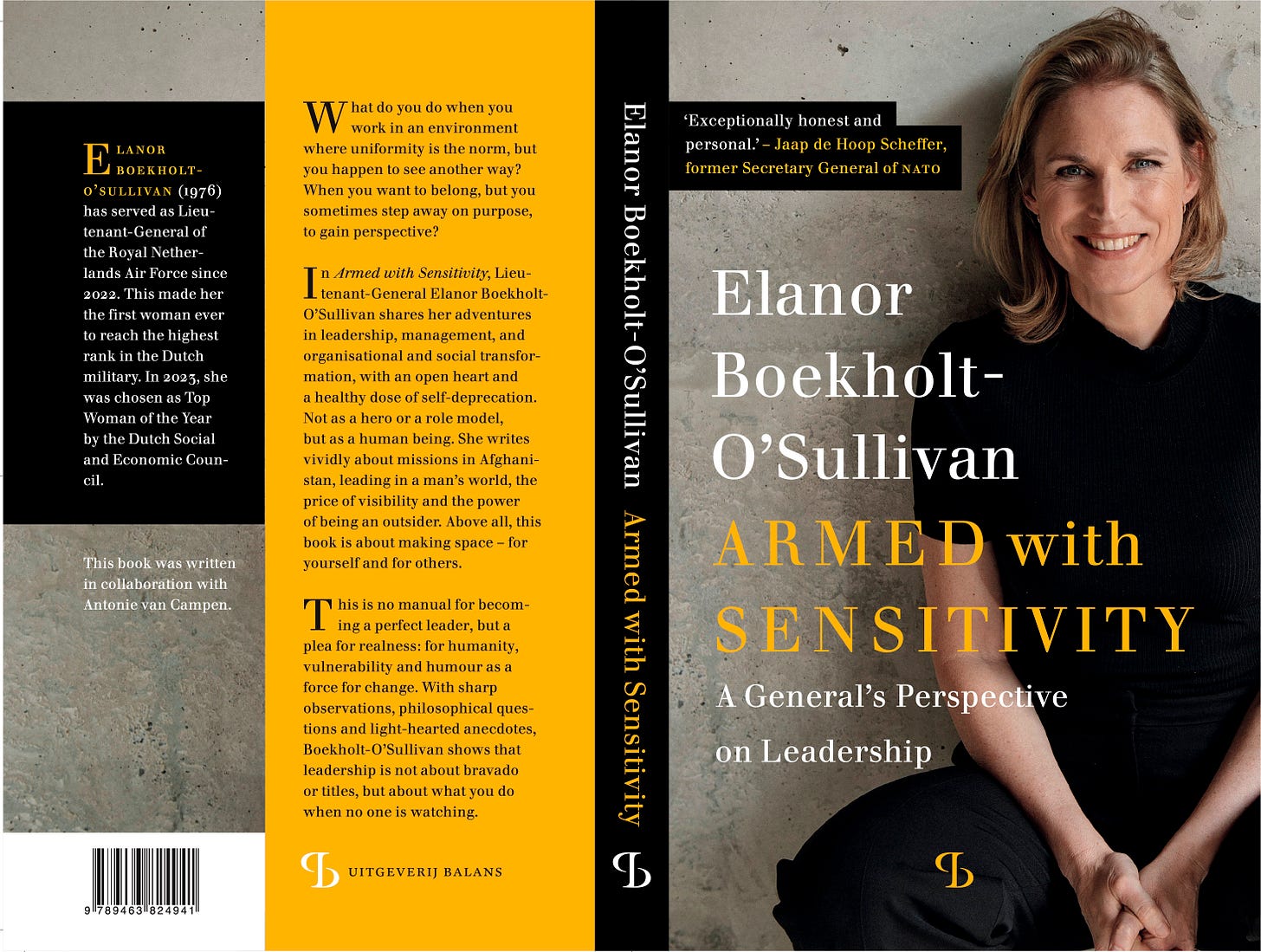

And now, she has published a book about her ideas. It’s called “Armed With Sensitivity: A General’s Perspective on Leadership.”

General Boekholt O’Sullivan has graciously offered to share an excerpt with us, today! Here she is, straight from her book (which you can purchase here):

“In the armed forces, but perhaps even more so outside it, military leadership is often associated with visibility. The image of the soldier as someone who is loud, powerful and fearless is deeply rooted. Leaders who are visible and loud, we believe, win wars and lead troops to victory.

But is that really the case? And more importantly, does this mean that you cannot be a good leader if you are less visible and loud? What if you observe more than you speak? What if you think before you speak, and prefer to listen rather than draw attention to yourself? Does that mean you cannot be a leader? Does that mean you cannot be charismatic? Or do we only attribute charisma after the fact to those who were successful?

My natural tendency to first observe was not always understood in my early years in the armed forces. Silence was quickly interpreted as doubt. Restraint. Or worse still: as weakness. In meetings, I felt pressure to say something, even when I knew it would be more useful to wait a moment; to listen, to understand, and only then to respond.

But that’s not always how it works. In many organisations, including the armed forces, visible leadership is often equated with audible leadership. Those who speak up get attention. And those who hesitate risk giving the impression that they have nothing to say.

Even during training courses, there is a strong focus on how often you speak up. How you ask questions. How assertive you are. Not just what you say, but above all the fact that you say it.

In a new position, you are expected to make your mark almost immediately. As if all that matters is that something changes drastically. Building on the work of your predecessor? In this culture, that feels like a sign of weakness. But is that justified?

Or are we confusing visibility with effectiveness?

I don’t think you have to be opposed to outspoken leaders – many of them may operate efficiently and achieve great things in that way. I also believe that being loud is not the same as good leadership. Sometimes it’s quite the opposite.

You see it time and time again in the workplace: a new leader who wants to do everything differently may be impressive on paper, but the team often thinks: ‘Here we go again... let’s just sit this one out, and then the next one will come along.’ It’s recognisable. And it’s a shame.

Because there, between the lines, you see where the strength lies: in continuity. In listening. In understanding what is already there before you decide to change it. The quiet forces in the workplace make the difference. Those who do the work behind the scenes. The quiet leaders see where it’s working and who is working. They create space, rather than fill it.

These are leaders who win in the long run. Not because they made an impression in the first week, but because after three years, they leave behind a team that has become stronger.

No grand gestures, no radical change of course. Just trust. Structure. Time.

And yes, sometimes you have to work harder to be taken seriously when you operate in that way. But you don’t recognise true leadership by the volume of the voice. You recognise it by the results and the way in which those results were achieved. And by how long those results endure when a leader is succeeded by someone else.

WHAT YOU DON’T HEAR

I remember a training course about fifteen years ago, when I was a major, in which a teacher took me aside after a day of lessons. ‘You need to speak your mind more,’ he said. ‘People want to see and hear that you are there.’ It sounded like well-intentioned advice, but to me it felt as if he was saying that my way of observing, listening and thinking was not enough and therefore not right.

Yet I decided to give it a try. I tried raising my voice (which still didn’t seem loud to me), responding more quickly and emphasising my presence more. I tried to play the active student that people seemed to expect. But it felt as if I was wearing a mask. And the more I wore it, the more it started to pinch.

Later, when I was leading larger teams myself, I began to notice something. The most effective team members were not necessarily the ones who talked the loudest. They were just as likely to be the quiet, thoughtful types. In fact, they complemented the more vocal types. They were more likely to spot details that others missed, make relevant connections that others didn’t always see and come up with solutions that were sometimes quite surprising and effective.

This got me thinking: why do we promote a culture in which visibility is so often the norm? Why do we associate visibility with trust, as if the two were inextricably linked? In missions, military personnel must be able to trust their leaders blindly. But trust is not necessarily built by those who speak the loudest or are the most visible. Loud and powerful leaders can initially inspire trust, I admit. But it can also be a mask. A convincing facade, with no depth.

As far as I’m concerned, charismatic leadership can exist without being linked to that tough, visible presence. It can just as easily stem from deep-rooted trust, built through consistency, integrity and the ability to listen. Sometimes the real power of leadership lies in what you don’t see. Not in fine words or grand gestures, but in the small actions that create space for others to do their work properly.

Take the special forces, who work inconspicuously and yet make all the difference. Or the people behind the scenes, cybersecurity people, who keep things running pretty much unnoticed. They remind us that success depends not only on what is visible, but also on everything that quietly contributes to it.

QUIET LEADERSHIP

My view of leadership changed fundamentally after reading Susan Cain’s book Quiet. The book felt as if someone had looked inside my head – and then written it down better than I could ever have done myself. I sent her an email to thank her. ‘Thanks to you, I’ll never have to write a book,’ I wrote. ‘Everything I ever wanted to say is already in your book – and better too.’ To my surprise, I received an invitation to visit the Quiet Leadership Institute in New York.

What I found there was clarity. Introversion is not an obstacle for which you have to compensate. It is a source of strength, provided you learn how to use it. The conversations that followed were not only about introverted qualities, but also about the interplay with extroverted characteristics. Not either/or, but both.

Yet something continued to nag at me. It was nice to feel recognition, but what could I do with it? The real issue was not within me, but in the organisation I work at. How do you ensure that people who do not put themselves in the spotlight, but do have something important to say, are given the space to do so?

How do we make the armed forces appealing to people who think they don’t fit in? Not by changing them, but by making space. For those who are quiet, but not invisible. For those who listen and only speak when it matters. For leadership that is not loud, but that works.

I decided not to stop at theory, but to make it more practical. I hired two trainers from the Quiet Leadership Institute [which no longer exists] and organised workshops for senior Defence colleagues who identified with the theme or were simply curious. The goal? To learn how to make better use of the qualities of introverts in your organisation.

We also organised a Quiet Leadership symposium. A conference at which introverted leadership would be given a face within the military context. With someone who had authority and respect, and whose story would touch people. I eventually found two such people: General Tom Middendorp, then Chief of Defence, and General Stanley McChrystal, author of Team of Teams. Both described themselves more as ambiverts or introverts rather than extroverts – something that visibly surprised many of those present. And that’s exactly why it worked.

The room was full. Participants had filled out a questionnaire about their personality in advance. Based on the results, they were assigned a seat colour: red for extrovert, green for introvert, blue for ambivert. A simple representation, but effective. Upon entering, you could see at a glance how the group was divided.

More than 90 per cent scored higher on extrovert than on introvert or ambivert. The latter accounted for only 2 per cent. Of course, you could question, how honest people are when filling in a questionnaire like this. Sometimes we say what we hope is true. Or what we think a good employee would say.

But it’s not surprising. In an organisation associated with action, visibility and speed, there are relatively few applications from people who prefer to have a bit of a think first.

And yet it is precisely this minority that sometimes deserves a microphone. Not to be loud, but to be audible. Leadership has more than one volume. And sometimes the power lies not in how loudly you speak, but in what you say, and when.

What I hoped to convey is that silence is not the same as passivity or absence. Silence is not passive. It is not doing nothing. It is giving space. So that others have the courage to say something.

The power of silence lies not in yourself, but in what it enables others to do. Not every good idea begins loudly. Some thoughts need silence to actually come into being. That insight, and the conference on introverted leadership that we organised, gave me the confidence to carry on building on my own way of working. Not forcing, but shaping. I deliberately started to create space. Not with spontaneous brainstorming in which the fastest wins, but by sharing topics in advance, so that the thinkers among us could also participate.

I allowed silences to fall. Not uncomfortably, but deliberately. I looked at who always spoke and who never did, and I tried to create space without pushing anyone into the spotlight. Slowly, it started to work.

People who had previously been silent began to speak. Not because they had to, but because they felt that they were being listened to. What started as a method became something bigger. A cultural shift. Diversity in personalities became tangible – no longer a wish on paper, but palpable in how the team worked.

At a meeting, a young colleague suddenly said: ‘I always thought leaders had to be loud. But you have shown that listening is more important.’ Simple words. But they struck a chord.

Ultimately, that is the heart of the matter: leadership has no fixed form. It can be loud or quiet. Visible or inconspicuous. Extroverted, introverted, or something in between. What matters is not the style. What matters is what it enables. For the team. For the mission. For everyone who contributes. And to tackle complex challenges, that is exactly what we need: not uniformity, but space. For differences. And for voices that don’t naturally rise to the surface unless you dare to be quiet for a moment.

What I learned is that introversion is not only an individual trait, but above all a quality that makes a team stronger. In a culture that often revolves around action, speed and visibility, an introverted approach brings something rare: calm, reflection and space. It is the ability to see patterns where others experience chaos. To listen before you judge. And to only say something when you really have something to say.

Extroverts bring something else. Something necessary. The ability to energise a group. To make the right decision at the right time, when others remain uncertain. To stand up, speak, and say, ‘Let’s go.’ That is not a facade, not a superficial show. It is leadership that you see and feel. On exercise, when there is an unexpected turn of events, or simply on Monday morning at eight o’clock when there’s no more coffee and no one is in the mood. That, too, is essential.

In the armed forces, we need that diversity of personalities just as much as we need diversity in gender, ethnicity and experience. The best teams consist of people who complement each other. It is precisely in the difference that the strength lies.

And perhaps that is the most important lesson: leadership has no fixed volume. It can be loud or quiet. Prominent or in the background. Extrovert, introvert, or simply human.

What matters is that it works. That people feel seen. That everyone is given the space to contribute, in their own way. To really get something done, you don’t need uniformity. You need an environment where differences are allowed to exist, and where being quiet is not confused with a lack of understanding. After all, silence is not a weakness if you know what you are saying with it. That, too, is a form of leadership. Armed with heart, not with noise.”

*

This is Susan writing again:

What moves me most about General Boekholt O’Sullivan’s reflections is not simply that they validate introversion — though they do — but that they restore something deeper: moral seriousness to the idea of leadership.

If this piece stirred something in you, you might reflect on these questions:

*When have you felt most effectively led — and what qualities did that leader embody?

*Do you associate authority with visibility? Where did that belief come from?

*How might meetings, conversations, or decisions change if space were intentionally made for quieter forms of thinking?

As always, we would LOVE to hear your thoughts. And so, I’m sure, would General Boekholt O’Sullivan.

Thank you for sharing this Susan. It helps me to soothe my worry about our own leadership in the United States currently. I loved her wording about introverts ..."prefer to have a bit of a think first." Aaahhh, that sits so well when looking to the path forward! Thank you General Elanor Boekholt-O'Sullivan! 😎💕

Susan, I will be rereading this more than a few times, and passing along to my daughters who share the qualities of introversion.

A funny story: When I taught, I had the following sign, written pretty small, but visible at the front of my classroom: Before you speak, ask yourself: Is it kind, is it true, does it improve upon the silence." It's an edited version of a talk attributed to a few different Buddhist philosophers. Well, I put the sign there for all the teachers who would come into my room, loud and chatty, always having something to say. But they never saw it as being about themselves. Self-reflection is challenging when you're always talking.

An important example: I want to recommend listening to and watching the police department chief of Minneapolis, Brian O'Hara. He was on 60 Minutes last night. That felt like a fine example of quiet leadership in action. He said what he had to say - no more, no less. In our times of loud, attention seeking behaviors, watching him almost made me cry. Though I'm quite sure many in Minnespolis, having a more up close experience with him, might disagree.