The case for a calmer and more intellectual life

A new book, and its lessons from ancient Egypt and beyond

But first: are you a vivid dreamer?

Our next Sunday Candlelight Chat is THIS SUNDAY, October 27, at 1 pm ET, and it should be extremely interesting. We’re hosting Lisa Marchiano, Deborah Stewart, and Joseph Lee, the authors, therapists and co-hosts of the popular podcast, This Jungian Life (almost 14 million downloads!). We’ll discuss their forthcoming book, Dream Wise: Unlocking the Meaning of Your Dreams, a definitive handbook on Jungian dream interpretation. And then…we’ll invite you to share your dreams, for interpretation by Lisa, Deb, and Joe!

We’ll send out log-in instructions to all Quiet Life members, TOMORROW. (Members can choose to watch quietly in real time; join in actively; and/or watch the recording later.)

Last week, we discussed how much we need the arts and humanities, and the reflective types who love them, create them, and engage with them.

This week, I’d like to introduce you to a fascinating new book, “Ad Astra Per Aspera”, that makes the case for a calmer and more intellectual life. This book was written by a Quiet Life member named Ouseph, who lives in a rural corner of India. (Ouseph would like to keep his privacy, and hopes that his work will speak for itself.)

Quoting biographies of famous people, Ouseph’s book argues that introversion and shyness are much more common in high achieving people than most people realize, and that introversion and even autism have played a very important role in the advancement of human civilization. The book also describes the educational culture of flourishing societies, from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia to modern South Korea and Singapore, arguing that modern Western educational and psychological attitudes are fundamentally flawed. Ouseph believes that Western education and psychology place too much emphasis on sociability, and that this has a detrimental effect on children’s intellectual cultivation and is the reason for the increase in social and emotional problems in children, including the steep rise in autism diagnoses in modern society.

This book is his labor of love.

(“Ad Astra Per Aspera” is a self-published e-book; it first appeared on Medium in 2017; today, it’s available via Amazon for 99 cents, and on Ouseph’s website you can download it for free.)

*

One of the fascinating questions that Ouseph’s book explores is: “Why do societies rise and fall?” and “What made the ancient Egyptians and Sumerians great?”

Here’s a short excerpt from the book, in which he focuses on the wisdom literature of ancient Egypt — and what it tells us about the pursuit of knowledge, gentleness — and the good life.

Here’s Ouseph:

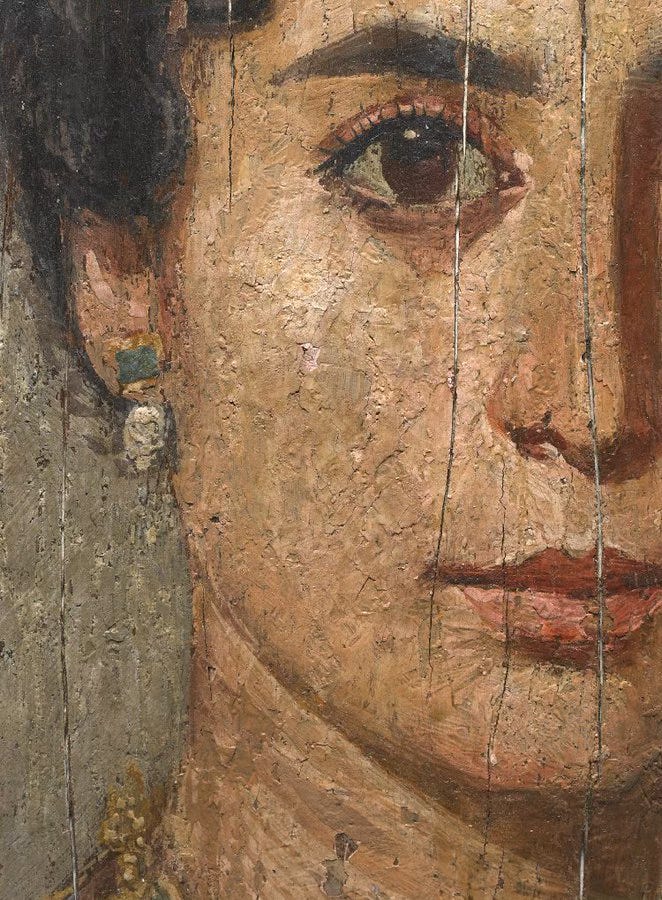

“Ancient Egyptians had one of the most remarkable wisdom traditions in history. In ancient Egypt, a genre of literature called Sebayt (wisdom books or Instructions) was used to teach pupils practical wisdom. The ancient Egyptians believed that these texts were composed by renowned people in Egypt’s history. (Whether these texts were actually composed by the historical figures mentioned in them is not known with certainty. It is possible that such attributions were used in order to provide these texts with more authority.) In ancient Egyptian society, these texts were used as didactic literature to teach the youth how to conduct themselves with wisdom and good sense. Egyptologists believe that Sebayt literature had an enormous influence on ancient Egyptian society. Its values are reflected in other facets of Egyptian life—for example, in funerary settings (the texts found at burial sites, like tomb autobiographies and the Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead, describe the same set of values). Moreover, some of the Sebayt texts were copied and studied by ancient Egyptian children for more than a millennia after they were composed, which is again an indication of their importance.

According to noted Egyptologist Miriam Lichtheim, the literary genre of Sebayt “was inspired by the optimistic belief in the teachability and perfectibility of man; and it was the repository of nation's distilled wisdom.” Ancient Egypt’s literature and other archaeological artifacts indicate a people who aspired to a highly refined way of life. Aiming to create thoughtful and gentle people, their wisdom literature emphasized such qualities as self-restraint, kindness, gentleness, and prudence in speech. Preoccupied with the idea of justice, Sebayt literature contains repeated exhortations of righteousness and compassion: be straight in speech and conduct, be charitable to the poor, be compassionate to the disenfranchised, be impartial while judging, and so forth. Another major theme in Sebayt texts is what Egyptologists refer to as the dichotomy of “silent man” versus “heated man.” The silent man is thoughtful, quiet, mild-mannered, and wise. The Sebayt texts contrasted the noble ideal of the silent man with the ignoble figure of the heated man. The heated man is talkative, unthinking, impulsive, and prone to emotional outbursts.

(Note from SC: I bolded the above bit because I find it so interesting. When researching QUIET, I found this kind of personality dichotomy in so many cultures - the one that stands out in my mind is the “Lakalai” people of Papua New Guinea, who noted the difference between “men of anger” and “men of shame”. Men of anger were, according to the anthropologist Edward Valentine (writing in the 1960s), “verbally expressive, physically mobile, and had a tendency to anger,” while “men of shame” were men of “silence, good conduct, knowledge, and art;” they took “care in observing customary proprieties, had a high degree of concentrated attention, and achievement in certain traditional skills.” However, in the Lakalai dichotomy, as I recall, there was no preference for one type over the other; both had value - which is how I see things, too.)

The Sebayt texts were often composed in the form of a father’s advice to his son. The text Instruction of Ptahhotep is an example of the Sebayt genre. The text is attributed to Ptahhotep who served as the vizier of ancient Egypt around 2400 BC. In the text, vizier Ptahhotep, for whom old age has arrived, is portrayed as providing his son with counsels of wisdom. The text has survived in four copies of which the copy of Prisse Papyrus is the most complete, dated to around 1900 BC. Renowned Egyptologist Battiscombe G. Gunn published one of the early translations of the Prisse Papyrus over a century ago, while also labelling it the oldest book in the world. The following quotations from Gunn’s translation aptly summarize the ancient Egyptians’ reverence for silence: “Silence is more profitable unto thee than abundance of speech” and “Be thine heart overflowing; but refrain thy mouth.”

Ancient Egyptians detested the life of a prattler. They believed that a person should speak sparingly, truthfully, and knowledgeably. They also believed that a person should be gentle in conduct. The following are a few excerpts from the Instruction of Ptahhotep (translation by Miriam Lichtheim):

If you are a man of worth

Who sits in his master's council,

Concentrate on excellence,

Your silence is better than chatter.

Speak when you know you have a solution,

It is the skilled who should speak in council;

Speaking is harder than all other work,

He who understands it makes it serve.

. . .

If you are mighty, gain respect through knowledge

And through gentleness of speech.

Don't command except as is fitting,

. . .

Be deliberate when you speak,

So as to say things that count;

. . .

He who steps gently, his path is paved.

Ancient Egyptians valued a calm disposition. The Sebayt texts taught the golden precept that it is more important to be a good listener than to be a good talker. Egyptians believed that the virtue of silence taught a person self-control and that it made him thoughtful and amiable. In the following passages, Ptahhotep describes how silence can even prevent quarrels:

If you meet a disputant in action,

A powerful man, superior to you,

Fold your arms, bend your back,

To flout him will not make him agree with you.

Make little of the evil speech

By not opposing him while he's in action;

He will be called an ignoramus,

Your self-control will match his pile (of words).

If you meet a disputant in action

Who is your equal, on your level,

You will make your worth exceed his by silence,

While he is speaking evilly,

There will be much talk by the hearers,

Your name will be good in the mind of the magistrates.

If you meet a disputant in action,

A poor man, not your equal,

Do not attack him because he is weak,

Let him alone, he will confute himself.

Do not answer him to relieve your heart,

Do not vent yourself against your opponent,

Wretched is he who injures a poor man,

One will wish to do what you desire,

You will beat him through the magistrates' reproof.

The Instruction Addressed to Kagemni is another text from the Sebayt genre. It has survived only partly. In it, a quiet and mild disposition is again exalted:

The respectful man prospers,

Praised is the modest one,

The tent is open to the silent,

The seat of the quiet is spacious.

Do not chatter!

. . .

Let your name go forth

While your mouth is silent.

Another wisdom text called the Instruction of Scribe Any contains the following advice.

A man may be ruined by his tongue,

Beware and you will do well.

A man's belly is wider than a granary,

And full of all kinds of answers;

Choose the good one and say it,

While the bad is shut in your belly.

The Instruction of Amenemope is a famous Egyptian literary work. It was composed around 1200 BC, and portions of it have survived in six copies. In the Instruction of Amenemope, the heated man is compared to a tree growing indoors without the nourishment of sunlight. It is destined to wither away. On the other hand, the silent man, who is of the gentle and prudent type, is compared to a fruitful tree growing under the nourishment of sunlight.

As for the heated man in the temple,

He is like a tree growing indoors;

A moment lasts its growth of shoots,

Its end comes about in the woodshed;

It is floated far from its place,

The flame is its burial shroud.

The truly silent, who keeps apart,

He is like a tree grown in a meadow.

It greens, it doubles its yield,

It stands in front of its lord.

Its fruit is sweet, its shade delightful,

Its end comes in the garden.

As the wise men of ancient Egypt correctly deduced, it is the quiet, thoughtful, and prudent who flourish in life while those who are loud, impulsive, and frivolous in behavior flounder. It is remarkable that the axioms of Egyptian wisdom literature remain true to this day.

Sebayt literature also stressed the importance of being just and honest. In the following passages, Ptahhotep reiterates an important precept of life:

Baseness may seize riches,

Yet crime never lands its wares;

In the end it is justice that lasts.

The Instruction of Hardjedef contains the following advice:

Cleanse yourself before your (own) eyes,

Lest another cleanse you.

Ancient Egypt’s educational culture and the values it imparted to its children, particularly its emphasis on nurturing refined, gentle, and thoughtful persons, may have played an important role in the extraordinary longevity of the ancient Egyptian civilization. The ancient Egyptian civilization reached its zenith in the New Kingdom Period (ca. 1550–1077 BC). In the 1st millennium BC, it went into decline and was repeatedly conquered by foreign powers. Yet, even as its power waned, those who conquered Egypt, in turn, became enthralled by Egypt's extraordinary culture, architectural grandeur, and legendary history. By the time of the great Greek philosophers of the 5th century BC, the pyramids of ancient Egypt had been standing for more than two thousand years.”

I hope you enjoyed this fascinating excerpt. If you have a friend who might be intrigued by Ouseph’s work, too, you can share, here:

And, if you’d like to discuss the above, please do leave a comment below! Here are some prompts, to get you started (but please feel no need to stick to the below questions):

*Were you surprised by what you learned about the value system of ancient Egypt?

*Do you agree with the idea of a dichotomy between the “silent man” and the “heated man”?

*What do you think of Ouseph’s idea that “nurturing refined, gentle, and thoughtful persons, may have played an important role in the extraordinary longevity of the ancient Egyptian civilization”?

You know I always love to hear your thoughts!

This all resonates deeply with me. I look forward to reading Ouseph's book! And I thank you again, Susan, for your immeasurable contribution to this....to finally hear and see the strength, beauty, and value of quietness. to finally have that acknowledged amidst all the noise and distraction, to have this community who speak the eloquent language of quiet silence.....such a gift.

This was absolutely fascinating. I love this post, and I too look forward to reading Ouseph’s book (bought before I finished reading the post!). I love Ouseph’s idea that “nurturing refined, gentle, and thoughtful persons, may have played an important role in the extraordinary longevity of the ancient Egyptian civilization”. This is a fascinating notion. And if I try to apply it to the present, I certainly see that many of the people that I admire the most are those who don’t feel the need to speak for the sake of speaking, and their sparse words are very thoughtful. These are also the people I tend to be most drawn to in social settings as well. Because their words or more intentional they also tend to be more interesting, insightful, and thought provoking. I believe that perhaps the people in our time with the characteristics described by Ouseph DO play a greater role, or even an outsized one, in our own “civilization” than we realize, we just don’t SEE them every day through the “noise and because our value system does not emphasize their importance in nearly the same way.