And Yet the Books

How to transcend our earthly tribalisms

The Quiet Life is read in all 193 countries and all 50 American states. We’re dedicated to bringing you an online oasis of Quiet, Depth, and Beauty.

If you’re new here, welcome! And, here are some previous posts you might enjoy:

*When You’re 94: Questions to Ask Yourself Right Now

*Are You A Highly Sensitive Person?

“Receiving something in my inbox from Susan is like curling up on a rainy afternoon and breathing out a sigh...bliss.” - Cindy P.

Dearest You,

If you’ve been here for a while, you know that I get on certain kicks, where I start reading a lot of a particular poet or writer or thinker, and then sharing with you. I think that the last time this happened, I kept sending you Kindred Letters full of Constantine Cavafy poems.

So right now, I’m reading the great anti-totalitarian poet, Czeslaw Milosz, who lived through the various horrors of the 20th century.

Here’s one of his gems:

*

And Yet the Books

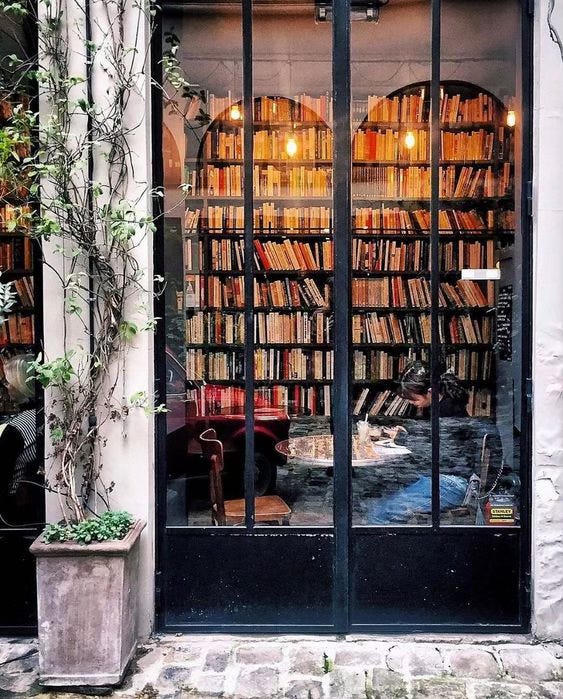

And yet the books will be there on the shelves, separate beings,

That appeared once, still wet

As shining chestnuts under a tree in autumn,

And, touched, coddled, began to live

In spite of fires on the horizon, castles blown up,

Tribes on the march, planets in motion.

“We are,” they said, even as their pages

Were being torn out, or a buzzing flame

Licked away their letters. So much more durable

Than we are, whose frail warmth

Cools down with memory, disperses, perishes.

I imagine the earth when I am no more:

Nothing happens, no loss, it’s still a strange pageant,

Women’s dresses, dewy lilacs, a song in the valley.

Yet the books will be there on the shelves, well born,

Derived from people, but also from radiance, heights.

Czeslaw Milosz

*

And oh there’s so much in this poem.

The bemused appreciation of dewy lilacs and songs in valleys. The great love of books, of course, and the great frailty of human society: its impermanence; its imperfections; the way it organizes itself into tribes that blow up the castles of other tribes, that burn their books.

But most of all it’s about the power of books to resist, to overcome, to stubbornly maintain their points of view, to outlive us all.

Because books are the ultimate product of the individual spirit. You can’t write a poem by committee, you can’t write a book by tribe. The more a book reflects the idiosyncratic perspective of its author, the better it will speak to you.

Milosz is often described as a poet of anti-totalitarianism. And totalitarianism, of course, is about many things. The denial of liberty and expression to individuals. The investment of all power in a ruling party or person. The insistence on seeing the whole world through a particular ideological lens, then bending everything to fit that lens. The division of humans into favored and unfavored categories. In Milosz’s time, there was Aryan vs. Jew, and proletariat vs. bourgeoise (where anyone proletariat was good, and anyone bourgeoise – including, in some regimes, the descendants of landowners or just people who happened to wear eyeglasses, which were thought to signify landowner adjacency) – deserved to die or be thrown in prison.

But most of all, totalitarianism is about a belief in the group over the individual. And I don’t know if this is the introvert in me, or something that runs even deeper, but all my life I have intensely loved individuals, and intensely mistrusted groups, specifically their capacity to descend into mob violence.

Of course, groups can do great things too, and of course, we all have our tribal allegiances, via family, religion, nationality, sports team, etc. For better and for worse, that’s part of what it means to be human. The word “kind” derives from “kin.” Humans seem to love their kin above all else. It’s from our kin that we learn how to love in the first place. We enter the world naked and bewildered, and our kin feed us and hug us and keep us warm.

And yet. And yet. And yet. We are first and foremost individuals, we are unique souls, we are made sacred by our very existence, and the books come from this individual spirit; they transcend our earthly tribalisms. They are “separate beings,” as Milosz puts it. Chances are that the books you’ve loved best weren’t written by members of your particular kinship groups. They were written by other humans - their soul direct to yours.

And this is how they can be, as Milosz says, simultaneously “derived from people, but also from radiance, heights.” This is why we love them so.

Before you go, some questions for you:

*What’s your reaction to Milosz’s poem?

*Tell us one or two of your favorite poets.

*My third-grade teacher told us that all storytelling is about the conflict between (a) the individual vs. nature, (b) the individual vs. him/herself, or (c) the individual vs. society. As you can see, I’ve never forgotten this! What do you think?

Please share your thoughts, by entering the comment section!

"Reading Susan’s Kindred Letters is one of the highlights of my week. This is coming from a person who subscribes to other newsletters then proceeds to never read even one of them.” - Curby A.

If you’d like to read more of Susan’s writing; participate in or watch her Candlelight Chats with incredible guests; share your own work and thoughts; or generally support our work, you can subscribe below.

And, if you’d love to join, but can’t afford a membership, we have full and partial scholarships! Pls email us at hello@thequietlife.net.

Czesław Miłosz... what a nice surprise...I needed to read the poem in Polish, my ( and his) native language to feel the poem in my bones and yes, it's about the immortality of the books and the human spirit...

I appreciate his poetry, yet my favorite author is Wisława Szymborska ( Miłosz and Szymborska were friends and have corresponded for a long time) and here is one of her poems:

A Few Words On The Soul

We have a soul at times.

No one’s got it non-stop,

for keeps.

Day after day,

year after year

may pass without it.

Sometimes

it will settle for awhile

only in childhood’s fears and raptures.

Sometimes only in astonishment

that we are old.

It rarely lends a hand

in uphill tasks,

like moving furniture,

or lifting luggage,

or going miles in shoes that pinch.

It usually steps out

whenever meat needs chopping

or forms have to be filled.

For every thousand conversations

it participates in one,

if even that,

since it prefers silence.

Just when our body goes from ache to pain,

it slips off-duty.

It’s picky:

it doesn’t like seeing us in crowds,

our hustling for a dubious advantage

and creaky machinations make it sick.

Joy and sorrow

aren’t two different feelings for it.

It attends us

only when the two are joined.

We can count on it

when we’re sure of nothing

and curious about everything.

Among the material objects

it favors clocks with pendulums

and mirrors, which keep on working

even when no one is looking.

It won’t say where it comes from

or when it’s taking off again,

though it’s clearly expecting such questions.

We need it

but apparently

it needs us

for some reason too.

Put very concisely and simply, my concern is for my children… now young adults. I feel so very disappointed in my generation. The forces of authoritarianism are large and systemic, individualism and the worth of it isn’t recognized. I’m very sorry. I’ve had a good life, but my thoughts are for my daughters, and honestly I am not too optimistic. I’m sure anyone reading this comment wonders what the hell I’m talking about, but I know exactly what I’m talking about.